By: Robert St. Martin

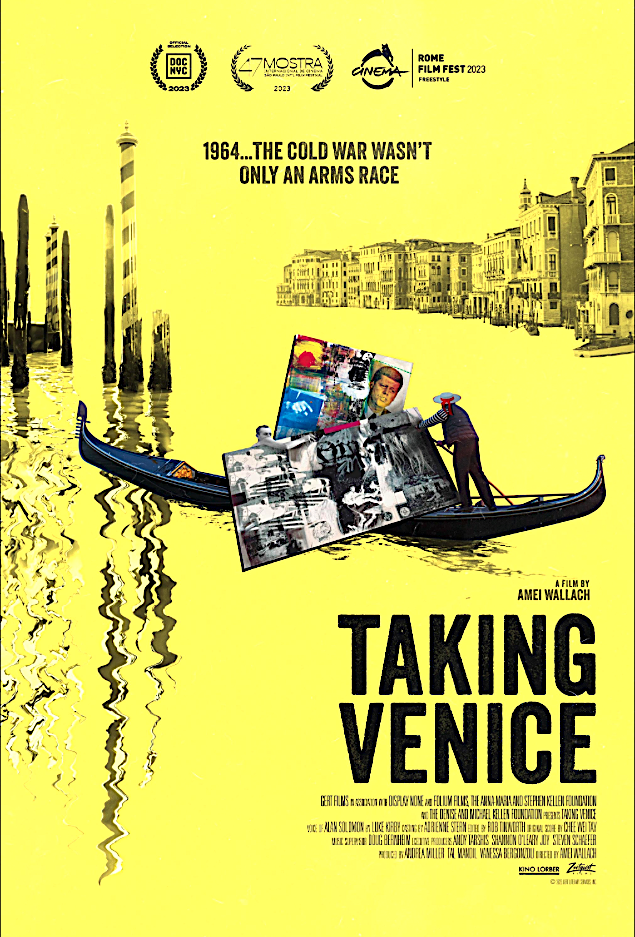

Los Angeles, CA (The Hollywood Times) 5/27/24 – Currently on screen at the Laemmle Royal Theatre in West Los Angeles and the Laemmle Town Center Theatres in Encino is Amei Wallach’s Taking Venice, an insightful documentary about how American artist Robert Rauschenberg managed to put the New York art scene of the 1960s on the map and displace Paris as the center of the artistic world. The film tells the story of the first time an American artist entered the Venice Biennale at the height of the Cold War. Determined to fight Communism with culture, Alice Denny, a Washington insider, Alan Solomon, an art curator, and Leo Castelli, a powerful art dealer, look to make artist Rauschenberg the winner of the Grand Prize at the Venice Biennale, which is the art world’s equivalent of the Oscars in cinema and the Venice International Film Festival.

From the opening frames, Taking Venice thrusts viewers into the turbulent waters of the 1964 Venice Biennale, where art and international politics clash under the guise of cultural competition. Wallach looks into a fascinating exposé on the U.S. government’s manipulation of the art world to counteract Communist influence during the Cold War. The documentary uncovers the strategic use of Robert Rauschenberg’s artwork to navigate geopolitical tensions, making every scene resonate with the thrill of a spy mission.

Central to the narrative are figures like Alice Denney, Alan Solomon, and Leo Castelli, who seem pulled straight from a spy novel. They strategically champion Rauschenberg’s groundbreaking style, steering them through a sea of conservative criticism within the art community. Their mission goes beyond artistic management, venturing into chess-like geopolitical maneuvering.

While the film is meant to focus on Cold War politics, it often finds itself more interested in the art and exhibits (which, to be clear, is fine, but it was almost like this should have been a two-part documentary that allowed the focus to be split.) Wallach moves back and forth, developing the scheme while simultaneously informing the audience of the art movement of the time as well as Rauschenberg’s contemporaries.

It doesn’t take long for Wallach to demonstrate that this isn’t the average archival footage and still picture documentary. While those are present, the film blends them together with modern footage in ways that showcase the art. A still photo in a sepia tone will merge with full color moving video to create a unique visual style. There are moments when newspapers in France or Italy are displayed, and then the language morphs into English to reveal the content for the likely American audience. These visual embellishments add a distinct style that makes it stand out from other historical documentaries.

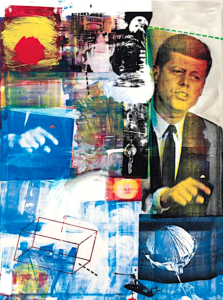

A band of sharp-witted American diplomats and art world players figured out how to manifest a win at the Venice Biennale for Rauschenberg, whose work mixed collage, painting, and silkscreen and sometimes utilized ordinary household objects, curios, and junk. This was the Pop-Art era, in which many exhibits, particularly in the US, prompted visitors to ask, “Is this really art?” Rauschenberg was one of the exemplars of the movement, along with Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenberg, and Andy Warhol.

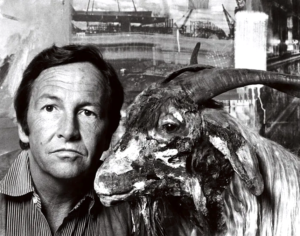

Prior to Venice, Rauschenberg had been criticized both at home and abroad as, in his own words, “a clown” or “a novelty.” But he was also becoming more popular and had begun to sell work for large sums of money, so it’s not as if he was Philip Glass still driving a taxi cap after Einstein at the Beach had premiered at the Metropolitan Opera. There is a mysterious inevitability to the way that certain cultural figures keep rising throughout their careers, and Rauschenberg had that kind of aura. He seemed like somebody already headed for the summit of the mountain who just needed a push to get to the top.

A combination of factors made Robert Rauschenberg the perfect candidate for special attention from the American government at the Biennale. The US had become a superpower, and President John F. Kennedy (who was prominently featured in Rauschenberg’s work and would be assassinated six months before the Biennale) was the most enthusiastic supporter of the arts that the country had ever had in the White House. The State Department under Kennedy wanted to establish that America was making unique, adventurous fine art that was meaningful and beautiful, wasn’t just being dumped in overseas economies like blue jeans and Coca-Cola and was proof of why people should be on Team America instead of Team Soviet Union.

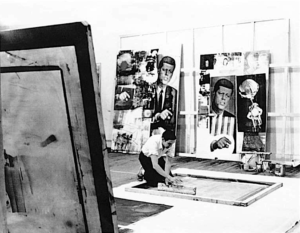

Alan R. Solomon was pushed to take charge of the U.S. participation in the Venice Biennale by Alice Denney, the former vice-commissioner of the U.S. pavilion at the Venice Biennale and wife of the deputy director for the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research. In the film, Solomon recalled: “Insisting on eight sizable one-man shows for artists, [he] soon ran out of space in the cramped American pavilion at the public gardens,” the site of all the official exhibits, where each artist was allowed to display only one painting. “With the agreement of the careless Biennale authorities, Solomon extended his show into a vacant American consulate building, much to the dismay of other nationals who had been denied such privileges.”

There were other improvisations as well. In the middle of the night, a construction crew built a makeshift addition to a courtyard-like area in front of the official site with a roof to protect against the elements (today, we’d probably call it a “pop-up exhibit”) where Rauschenberg’s work could be ported over from the auxiliary site, to neutralize gripes about his stuff being shown outside of the official exhibition venue. The strategy was to get people to experience more of Rauschenberg than any other artist at the Biennale.

Taking Venice jumps around in time to explore Rauschenberg’s development as an artist and person. There are detours about various subjects, including Rauschenberg’s long romantic relationship with fellow painter Jasper Johns and the “experiments and collaborations” he did at North Carolina’s Black Mountain College with the likes of composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham. Interestingly, Merce Cunningham and his dance troupe did ultimately show up in Venice, staging a performance the night before the awards deliberation that became the hottest ticket in town. The costumes and stage set design were by Rauschenberg. Although raised with a conversative Protestant religious upbringing that forbade dancing, Rauschenberg and his art is often “performance art” in which he himself danced at times. These interludes take the focus off the US government’s efforts to tip the exhibition in Rauschenberg’s favor.

Alice Denney (who is now 100 years old) tells the filmmakers, “We might have won it anyway, but we really engineered it.” Rauschenberg himself later questioned the political agenda that propelled him into the top spot. That his victory was obtained through a government-financed PR machine rather than achieved organically would seem to contradict the US narrative of America’s bright and shiny newness trouncing the ossified gatekeepers of Europe in a merit-based contest. The movie skates over that irony instead of digging into it.