By Robert St. Martin

Glendale, California (The Hollywood Times) 02/03/2024

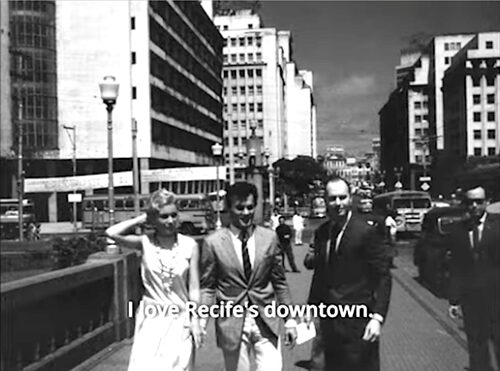

This week at the Laemmle Glendale Theatre is an opportunity to see Pictures of Ghosts (Portraits Fantômes, 2023), written and directed by Kleber Mendonça Filho – a film about his hometown of Recife in northeast Brazil. Recife is a large metropolis and the of the state of Pernambuco with a population of 4 million inhabitants and distinguished by its many rivers, bridges, islets, and peninsulas. Mendonça is best known here as co-director of the dystopian 2019 quasi-Western Bacarau (which starred Udo Kier and Sonia Braga), his prior feature films are set in Recife and were shot there, on occasion in the apartment in which the 53-year-old director grew up.

The documentary is divided into three parts: The first is about his childhood home, with particularly affectionate memories of his mother, a progressive political activist who informed his sensibility and his conscience and who died in her early fifties. Home is clearly where filmmaker Kleber Mendonça Filho first started out making home movies as a teenager. He includes clips from the crude horror movies he made as a boy, and the more polished ones he made in his adulthood, and we recognize archways and window in the apartment.

His childhood apartment is the locus of the first part of this poetic memoir-essay about place, cinema, and time. Twice renovated by his historian mother, the apartment was the site of his first early imaginative forays behind the camera and appeared in his first two features – Neighboring Sounds (2012) and, four years later, Aquarius. Mendonça’s native city of Recife has also been subject to similar remodeling or redevelopment, as shown in the second and third parts here, through the decline of its cinema houses. As they fall into dereliction, it feels like a form of collective dementia, robbing its citizens of a shared cultural continuity.

In Neighboring Sounds, Mendonça had an almost diagrammatic way of shooting his street and continues in the same vein here. Interweaving his family’s history with home-video excerpts and his later feature-film deployments, it’s as if he is trying to fix the essence of the place. Nico, the long-deceased dog next door, is resurrected thanks to clips from Mendonça’s debut, in which his incessant barking became part of the plot. Art can be an act of resurrection – or an exhumation: a bleary inexplicable phantom figure appears in a negative of the director’s living room, though it is not his mother who died aged 54 of cancer. The director’s sleepy voice sifts this flotsam of art and life. “It may seem like I’m talking about methodology, but I’m talking about love.”

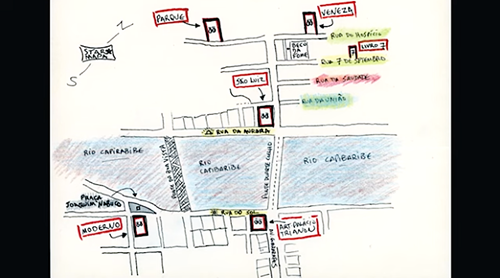

Mendonça’s pursuit of the past then heads out into downtown Recife, in search of more ghosts. In the movie’s second part, we go on a tour of Recife’s film culture, mostly by way of now-closed movie theaters, two of the most-missed ones once facing each other across the Capibaribe river. Now-bare cinema marquees, glimpsed in old photos, are timestamps for the city. As a filmmaker, Mendonça was educated in these places; we see him talking, in more archive footage, to “Mr. Alexandre”, the projectionist at the Art Palacio cinema who talks about locking it up on its final night “with a key of tears.”

These now-decrepit buildings are repositories of the country’s cultural history. The Art Palacio, for example, was once earmarked as an outlet for UFA, the Nazi propaganda cinema arm seeking to tighten its grip on the sympathetic Brazilian regime in the 1930s. German dirigibles such as the Hindenburg apparently visited Recife regularly.

Using still photos and archive footage, the director makes wordplay out of marquee titles “’My Name is Nobody’ … ’My Name is Earthquake,’” he intones, conflating the then-now-playing Spaghetti Western with the coming attraction boasted underneath. Quite revealing was his early 2000 interview with the protectionist who screened The Godfather for months until he couldn’t stand the film anymore.

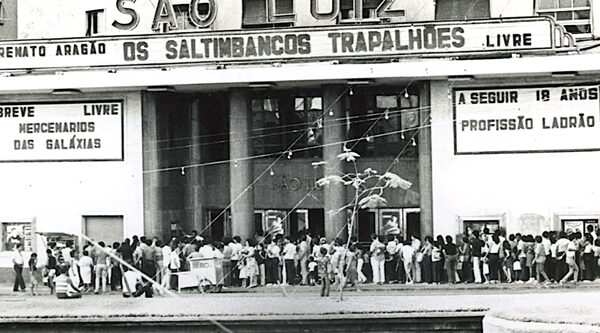

The film’s third part focuses on cinema as a site of worship: literally, in the case of several theatre auditoriums later converted into evangelical churches. In fact, the still-extant São Luiz theater was built on the site of a former church. On the ground where an 1838 Anglican church once stood, almost a century later, when British influence in Brazil had waned, up went the São Luiz, whose interior is resplendent in Fleur-des-Lis motifs. It has reverted to being an evangelical church at the present time. Mendonça is hardly the first to make the comparison and, with the relationship between cinema and religion in Brazil only cursorily sketched here. The old cinema faith isn’t likely to see a resurrection in Recife, with the city’s dynamism (and presumably the multiplexes) having migrated to other districts, and digital distribution now coordinated from São Paulo.

In the fictionalized coda at the end of the picture, the director takes a cab ride and tells his driver he manages a movie theater which now is an art house cinema. The larger issues one finds in this film are the huge impact of American movies on Brazil and much of the world, as well the enormous distribution system that the American movie studios had in the past. All that has changed in the digital age: Movie palaces are no longer in vogue, but the viewership patterns have changed. Many of Recife’s old movie theatres have been torn down and so only the surviving images tell us about these “pictures of ghosts.”