By Robert St. Martinez

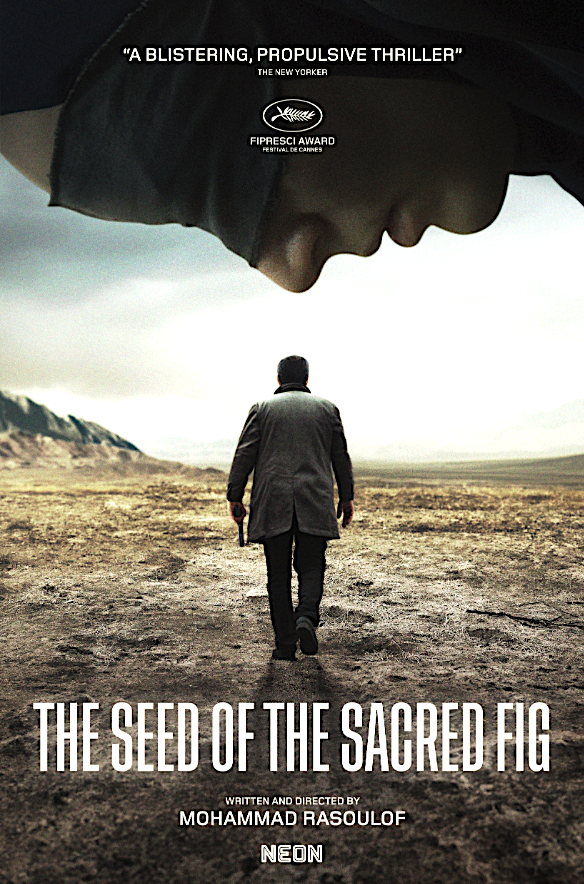

Los Angeles, CA (The Hollywood Times) 12/13/24 – Opening in selected theatres in Los Angeles this week is Mohammad Rasoulof’s The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Germany/Iran, 2024). For many viewers of Iranian cinema, the droll, often elliptical films of Jafar Panahi emerged as defining works about Iran under its theocratic tyranny. But this latest from Panahi’s fellow survivor of persecution, Mohammad Rasoulof, shows the equal power of the starker drama in its story of division and complicity within the country’s privileged classes. The film graced the Cannes Film Festival six months ago (winning the FIPRESCI Prize) with Rasoulof freshly escaped from his country and officially exiled. The Seed of the Sacred Fig wrenchingly pits an investigating judge and his wife against their two dissenting daughters, who are appalled by brutal crackdowns on protesters in Tehran.

Mohammad Rasoulof is a fugitive Iranian director and wanted by the police in his own country, where he has received a long prison sentence and flogging. The Seed of the Sacred Fig starts out in the modern world of Instagram reels and YouTube, composed in the complex and oblique style that we have got used to in Iranian cinema in films by Asghar Farhadi: a world of subtle, realist implications that has arguably replaced the fashion in Iranian cinema for the poetic and the sublime. (Rasoulof’s mysterious parable Iron Island from 2005 is a good example.) Here Rasoulof bookends the fictional narrative with real footage from the protests in Iran following the murder of Mahsa Amini, an Iranian Kurdish woman, in Tehran police custody on September 16, 2022.

The film takes its title from a species of fig tree, the ficus religiosa that envelops its tendrils around another tree. It proceeds to weave its tendrils around and around and around until it appears that it has rendered the tree incapable of escaping. The sacred fig then slowly strangles the tree to death and spreads its seeds. The sacred fig is the controlling metaphor for theocracy in Iran and perhaps not the most subtle title for Mohammad Rasoulof’s almost 3-hour film. It’s apt for a film that is not exactly subtle but is an unapologetic piece of political art, bookending its fictional narrative with real footage from the protests in Iran following the murder of Mahsa Amini, the Iranian Kurdish woman, in Tehran police custody on September 16, 2022.

The audience knows it – the footage of real-life protests seen in the film make it extremely clear that the questionable promotion Iman (Missagh Zareh) has just received is going to be problematic for his family. They are expecting material gains, such as a three-bedroom apartment in a building exclusively occupied by government workers and their families. But instead, the crushing reality of what Iman’s job means in its execution unravels the entire family spectacularly.

Iman (Missagh Zareh) is an ambitious lawyer who has just been promoted to state investigator – one step short of being a full judge in the revolutionary court. He gets a handsome pay rise and better accommodation for his family: wife Najmeh (played by actor and anti-hijab protester Soheila Golestani) and two student-age daughters (Setareh Malek and Mahsa Rostami). His wife Najmeh dotes upon him, and they savor the prospect of a bigger apartment and other rewards for his loyal service. But their daughters, university-age Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami) and younger Sana (Setareh Maleki), stay glued to social media videos of government attacks on protesters, shown repeatedly in harrowing clips in mobile phone-vertical shots.

It’s not that Iman doesn’t know the reality of what the justice system looks like in Iran. He has been part of that system for 20 years and knows what the system tells everyone: that it simply exists to enforce the will of God as written down. But there was always a level of discomfort between him and the need to be signing an execution warrant simply because the prosecutor wants him to. Very soon Iman is forced to sign execution orders because the secret police have arrested too many protesters. The system demands efficiency, ruthless efficiency. So, he signs them. He feels bad at the beginning, but he keeps signing them.

His wife Najmeh (Soheila Golestani) supports him, citing the stress of his position, the responsibilities on his shoulders, of how he was a better father to their two daughters Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami) and Sana (Setareh Maleki) than her own father was to her. But the rising toll of the protests breaks down any semblance of trust and faith between Iman and the women of his family as his true self, cracking down on protestors fighting for a better future, turns homeward.

Theirs is still a loving family, with warm memories; in one cozy scene, Najmeh and her girls groom and chat. But they’re primed for a generational clash, and the mounting dissonance between the young women’s democratic views and the parents’ hold-the-line conservatism becomes a microcosm of the archaic authoritarian regime ignoring its citizens’ will to be free. Rezvan and Sana are finally drawn directly into the turmoil of the latest protests when Rezvan’s friend, Sadaf (Niousha Akhshi), is wounded by a buckshot, and they smuggle her into the apartment for her safety.

The attack on Sadaf is shown in lingering close-up, realistically gory with her eye swollen shut – the face of an innocent victim of violence that any supporter of the regime is condoning. But an equally strong moment comes when Rezvan confronts her father at the dinner table and says, baldly, he’s wrong, and too close to the problem to see it. “Normal people who want a normal life and freedom” is, in Rezvan’s words, at the root of the protests, not some conspiracy of ill-defined “enemies” that her father flimsily maintains.

Accusations fly back and forth between the daughters and their protective mother, who’d rather that her children had never socialized with the likes of Sadaf but still asks a friend with a high-placed husband to ascertain Sadaf’s whereabouts in custody later. Throughout, Rasoulof is plumbing the individual moral decisions faced by citizens under this regime much as he did in There Is No Evil (2020) and its four stories circling capital punishment.

Rasoulof’s direction, Pooyan Aghababaei’s cinematography, and Andrew Bird’s kinetic energy all come together in some truly riveting sequences – a car chase in the Iranian desert and the hush whispers of a woman recording an instance of police brutality are particular standouts. the film serves as a warning against because while it’s specifically an indictment against the regime currently in power in Iran, its impact deserves to be understood on a broader scale.

“Over there we will become the family we were,” Iman says at one point when explaining a move to the countryside where he grew up. The tortuous phrasing is a concise statement of conservative purpose: Family and state returning to some imagined prior perfect form. It’s no wonder that Rasoulof opted to flee the country upon learning that authorities were onto his film production and would soon carry out his pending sentence of imprisonment and flogging. But his film deserves to be regarded on its own terms, as an eloquent record of and warning to a regime clinging to power at the expense of freedom.