By: Robert St. Martin

Los Angeles, CA (The Hollywood Times) 6/4/20204 – Currently on stage at the Los Angeles Theatre Center with the L.A. Latino Theatre Company is Oliver Mayer’s new play Ghost Waltz.

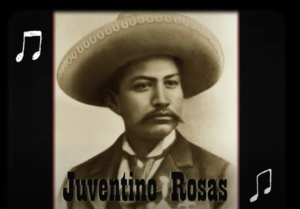

Developed in Latino Theater Company’s Circle of Imaginistas playwriting group, this new play is a boldly original recovery of Juventino Rosas (1868 –1894), one of Mexico’s most significant composers – an Indigenous musician whose life story has gone untold and whose works have been attributed to Europeans. The play follows the life of Rosas from his father’s early death to his friendship with ragtime genius Scott Joplin.

It’s a mix of music, magic, drama, passion, spirituality and dance in a celebration that explores the lives of people of color during the emerging Americas of the late 19th century and their ghostlike impact on our own lives today. Directed by Alberto Barboza, the play opened at Los Angeles Theatre Center on Spring Street on April 25 and runs through June 2. Tickets are still available for the very reasonable cost of $10.00 at https://ci.ovationtix.com/28125/production/1191647.

Ghost Waltz is told with great imagination and a wonderful score of waltzes, polkas, classical song, opera and ragtime. I found the play and its moving story to be one of the best plays I have ever seen this year in the way it highlights the best of diverse storytelling. Concert violinist and composer Quetzal Guerrero takes on role of the forgotten indigenous Mexican musician Juventino Rosas who plays the violin magnificently and composes waltzes in the style in vogue in the late 19th century.

Opera soprano Nathalie Pera Comas is the Mexican opera singer Angela Peralta, known as the “Mexican Nightingale,” singing Bellini, Donizetti, Verdi and Johann Straus the Younger, who was best known for his waltzes and light operas. Together the two Mexican performers have a story so rich and moving that it certainly deserved to be retold as this musical stage play.

Juventino Rosas meets ragtime master composer Scott Joplin in New Orleans after leaving his stint as a musician in a Mexican military band. Joplin is played by Ric’key Rageot, an award-winning musician and pianist who has performed with major pop stars like Madonna, Christina Aguilera, Cher, and Jill Scott. You can figure that some combination of these three individuals – set on collision courses in the same 100-minute play – definitely find a way to make some beautiful music together.

The cast of talented musician/actors is supported by Eduardo Robledo as Don Jesus – Juventino’s father, Argentine actor Cástulo Guerra as Professor Zeiss of the Conservatory, Ariel Brown as Bethena (wife of Scott Joplin), and Monte Escalante as Marie Laveau (New Orleans clairvoyant and voodoo queen).

Juventino Rosas’ waltz “Sobre las Olas” (“Over the Waves”) is perhaps the most famous song of its generation. Now, more than 130 years after it was written, the tune still feels immediate – sweeping, dreamy, and above all, supremely sure-footed. Every note is both rooted and soaring, coaxing even the wallflowers to dance and sway. It is easily on par with his contemporary Johann Strauss Jr.’s masterwork “The Blue Danube”—to the point that Strauss Jr. is often mistakenly credited with having composed “Sobre las Olas.”

Rosas was indigenous, dark-skinned in his photographs, and young. Proudly Otomí, an ancient people known to be great warriors, he and his family played music for coins on the street in Mexico City in the 1880s. It was a time of great change: The French and Austrian attempt at colonization had failed in spectacular fashion, but vestiges of European culture were everywhere.

Beer and polkas became core to the Mexican identity. Rosas embodied this moment in time. Yet, even as his famous waltz took the world by storm, he found himself having to prove his authorship. Losing the battle for the song’s royalties was just one indignity of many to come. In his own epoch as much as ours, Juventino did not fit the frame of the composer of “Sobre las Olas.” How could someone like him have written something so elegant, so graceful, so very Viennese?

There is precious little historical information to be found on the man himself. Part of a musical family, he was a violin prodigy who studied for a short time in conservatory before joining the world-famous Mexican Marching Band. Besides his famous waltz, he composed popular salon music, seductive polkas, and mazurkas for the piano. The wife of Mexican president/dictator Porfirio Diaz gifted him a grand piano for his genius, and his music was played throughout the Americas and in Europe, then and now.

Rosas was the same age as Scott Joplin, the undisputed “King of Ragtime,” a Black man whose musical oeuvre was similarly buried or forgotten alongside his life story until the 1973 movie The Sting used his song “The Entertainer,” and an expectant generation of music lovers recovered his ocean of rags and waltzes (one of which quotes a Rosas melody). How wonderful it was to discover that both Rosas and Joplin were both in Chicago in 1893 for the World’s Fair! Two young men of color, musical “virtuosi,” at the beginning of their heroes’ journeys, undaunted by the odds against them, with visions of as-yet-unwritten operas and symphonies dancing in their heads.

An opera singer originally from Mazatlán named Ángela Peralta, another of Rosas’ musical colleagues (and a possible love interest), also helped open up his story. Known to the world by her nickname the “Mexican Nightingale,” she was brown-skinned and indigenous like Rosas. Unlike Rosas, she hid her dark complexion beneath white face powder.

In many ways, Peralta was the opposite of Rosas: elitist, self-conscious, Eurocentric. A soprano, she played La Scala and other European opera houses, as well as toured the Americas – always under the mask of whiteness. Yet, despite her different philosophy of dealing with casteism and racism, the “Nightingale” ultimately endured the same fate as Rosas.

She studied at the Conservatorio Nacional de Música in Mexico City. At 15 she made her operatic debut as Leonora in Verdi’s Il trovatore at the Teatro Nacional in Mexico City. Accompanied by her father, and financed by a wealthy patron, Santiago de la Vega, she then went on to study singing in Italy under Leopardi.

On 13 May 1862, she made her debut at La Scala in with an acclaimed performance of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. She sang Bellini’s “La sonnambula” before King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy at the Teatro Regio in Turn where she received 32 curtain calls.

Between 1863 and 1864, she sang in the opera houses of Rome, Florence, Bologna, Naples, Lisbon, Madrid, Barcelona, St. Petersburg, Alexandria, and Cairo. The Second Mexican Emperor Maximilian Hapsburg of Austria invited her to return to her country to sing in the National Imperial Theatre, and in 1865 she accepted the invitation. In 1866 she sang before Maximilian I of Mexico and Charlotte of Belgium and “Chamber singer of the Empire.” In December 1866 with the downfall of the Second Mexican Empire imminent, she returned to Europe, performing in New York City and Havanna.

Her famous opera troupe arrived in the port city of Matzatlán, where they were to perform Il trovatore and Aida. The city of Mazatlán prepared an elaborate welcome for her. Her boat docked at a pier decorated with garlands of flowers, and she was greeted by a band playing the Mexican National Anthem.

When her carriage arrived, her admirers unhitched the horses and pulled it themselves to the Hotel Iturbide, where she once again saluted the crowds from her balcony. However, within a few days, she and 76 of the troupe’s 80 members were to die in the yellow fever epidemic that swept the city shortly after their arrival.

The famous opera house in Matzatlán was dedicated to Peralta after her death. Originally built in the late 19th century, the Teatro Ángela Peralta is a landmark of downtown Mazatlán with a tumultuous past. Over the years, it served as a boxing arena, movie theater, and opera house, before falling into decline, but live performances are still at the intimate 841-seat venue.

It just so happened that when I attended a performance of “Ghost Waltz” last night, I ended up sitting next to the great-grand niece of Ángela Peralta and we talked about her family’s memories of the icy-cold soprano who was one of Mexico’s most famous sopranos in the 19th century.

Ghost Waltz is a moody dramatic dive into the life of a violinist whose celebrated waltz got him mistaken for Strauss is as interested in questions of heritage and appropriation as it is in the biography of its historically ignored central character. Alberto Barboza’s production looks truly lovely on stage at the Los Angeles Theatre Center – and rapturously melodic but it leaves one with a nostalgia as fleeting as the spirits of the dead who populate the play.

Oliver Mayer’s play begins in dream form, with young Rosas in huaraches and white cotton, dancing to the waltz in his head, while the world circa 1890 was crashing all around him. Despite the tumult, he danced with calm and purpose, as if following the tune toward an as-yet unrevealed destiny.

Many years ago, Oliver Mayer wrote the libretto for an opera called “America Tropical” about the great 1932 mural by David Alfaro Siqueiros on Olvera Street in Los Angeles that was literally whitewashed by the all-white city council and town fathers for its political content. Not only was the image taken forever from us, but the artist was deported, never to return.

The center figure of the mural? A 14-foot-tall Indio crucified on a double cross, facing City Hall, foretelling the fate of his violent erasure, the double injustice of past and present bigotry.

Today, the “America Tropical” mural lives in a liminal state on Olvera Street. Years of California sun beating down on the whitewashed wall have thinned the cover-up, destroying the mask, allowing Siqueiros’ original images to ghost through.

Oliver Mayer feels that “As a playwright, my job is to shine a light on these layers of whitewash hiding the lives of Rosas and so many others like him. The damage cannot be undone, but there is a chance at recovery and a story to tell in the ghosting through of our history, and our mystery.” Certainly, Mayer’s intention in writing Ghost Waltz succeeds in unveiling the white washing of Mexican culture still so prevalent both here in the United States and in Mexico as well.