By Robert St Martin

Los Angeles, CA (The Hollywood Times) 6/16/24 – Last evening at the Billy Wilder Theatre of the UCLA Hammer Museum in Westwood, there was a screening of beautifully restored print of Marva Nabili’s masterful The Sealed Soil (Khak-e Sar Beh Moh, 1977). It is part of UCLA’s month-long Celebration of New Iranian Cinema. The Sealed Soil was shot clandestinely during a six-day period some time in 1976 before being smuggled out of the country for post-production. It is a significant film that helped pave the way for the Iranian “New Wave” of the 1960s and 1970s. Marva Nabili was one of the most important pre-Revolution Iranian women directors. It may surprise a few, especially given the number of female directors that have come to prominence in the ostensibly more restrictive post-revolution era, but only three features were made by women prior to the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

The Sealed Soil is an austere, emotionally muted yet deeply affecting portrait of a young woman caught between tradition, modernization and her own growing sense of self. It focuses on an 18-year-old named Rooy-Bekheir (played by Flora Shabaviz) who lives with her parents and an adolescent sister in a small village in Southeast Iran largely bereft of even the basic amenities of modern life. A sense of change is in the air, however, as the villagers have been asked to leave their mud-brick homes and relocate to apartment dwelling in order to make way for a medical clinic. It is important to remember that this story takes place two years before the Shah was deposed with the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

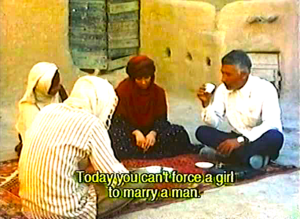

Rooy-Bekheir has other things on her mind. She is considered way past marriage age. The village elder once reminds her that her mother was wed off at age 7 and had already given birth to four children by the time she was eighteen. She is being coerced to consider a proposal. She is told, in so many words, that she is in a much better position than women of earlier generations. In a telling moment late in the film, she quietly takes offense when the modern, western-attired teacher of her sister asks her whether she happens to be the mother of one of her classmates (an earlier shot depicted her clandestinely learning how to read). The kind of change that would benefit Rooy-Bekheir is clearly not in the offing.

The film opens with an Albert Camus quote that anticipates the protagonist’s troubled and conflicted state of mind. Visually, Director Nabili and Director Photography Barbod Taheri convey this impression by often situating Rooy-Bekheir at the gated entrance of the village and capturing her through the opening. Other than a couple of brief panning shots, the film is primarily rendered through static tableau compositions, which again suggest a sense of stagnation and frustration. Director Nabili cites the work of Robert Bresson as a major influence but those who know Iranian cinema will also notice the significance of Sohrab Shahid Saless’s 1974 Still Life on her style.

In the film’s most striking scene, especially in the context of Iranian cinema, Rooy-Bekheir takes off the top of her traditional dress during a rainstorm, cherishing a brief moment of release. At another point, however, she attempts to harm the domestic pets and starts crying in a hysterical fashion (this episode lands her a visit to the local mystic healer, whose methods provide the film with its only comedic element). She may not have any control over her fate but still tries to make room for moral victories along the way.

Although its extent was governed by the conditions under which the film was made (it was shot MOS or “without sound”), the exaggerated sound-design reminds one of Robert Bresson. The only non-diegetic sound used in the film is a folk song that on one occasion briefly accompanies the protagonist during her daily journey to the nearby stream. The use of available light and grainy 16mm stock, which was most likely what Nabili was employing for her television films that she was making in Iran at the time. This only adds to the painterly quality of the work.

The film’s poetic tone, sparse dialogue and focus on its heroine’s daily life is comparable to Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman (1975). Nabili has had an interesting life and career. She studied painting at the Tehran University during the early sixties—in this case, her compositional sense and a keen eye for the quotidian suggest an affinity for Vermeer—before appearing as an actor in Siavash in Persepolis (1965) for the French-educated female director Fereydoun Rahnema. She subsequently studied cinema in London and New York before returning to Iran in the mid-seventies to helm a series of hour-long television films based on traditional folktales. This opportunity allowed her access to the equipment and the location (the village of Ghalleh Noo-Asgar, according to the film credits) required for the film.

Marva Nabili is known for American Playhouse (1980) and Nightsongs(1982). In an interview Marva Nabili explains about how the film The Sealed Soil got made: “I studied in New York, and I’ve lived in New York. I went to Persia to make this film. I was treated rather badly. I could not find any money for the film. They didn’t know me and especially because I was a woman, [they] had no confidence in [me]. So what I had to do was to work for television. I made a children’s series – fairy tale stories – and by that money I managed to make this film. It was made in a very low budget: thirty-five thousand dollars. And it was made in 16mm because I didn’t have the money [to shoot in 35mm].”

Marva Nabili was present for an insightful Q&A at the Hammer after the screening of her film with this restored print done by the UCLA Film & Television Archive with partial funding from the Farhang Foundation: The mud-brick village (built with materials better for handling the desert heat) than the cement apartments being build and that the village chief is encouraging the villagers to purchase and relocate into the “new town,” abandoning their farmland and cattle. At the time of film was shot in 1976, the Shah’s government was promoting agri-business companies to take over the land and modernize agricultural production – a plan that ultimately failed.

Asked about her style of using long shot sequences that focus on the environment, she responded: It’s a tradition I’ve picked up from Persian miniature and poetry which I have sort of transferred into cinema. It has nothing to do with the environment as much as it has with trying to make the audience to see something as a whole and depict lesser things themselves and figure out. I’ve tried to use the Brechtian theory, [combining it with] my own culture – miniature painting and poetry. All I’m doing is putting a distance between the audience and the happening.”