By Robert St. Martin

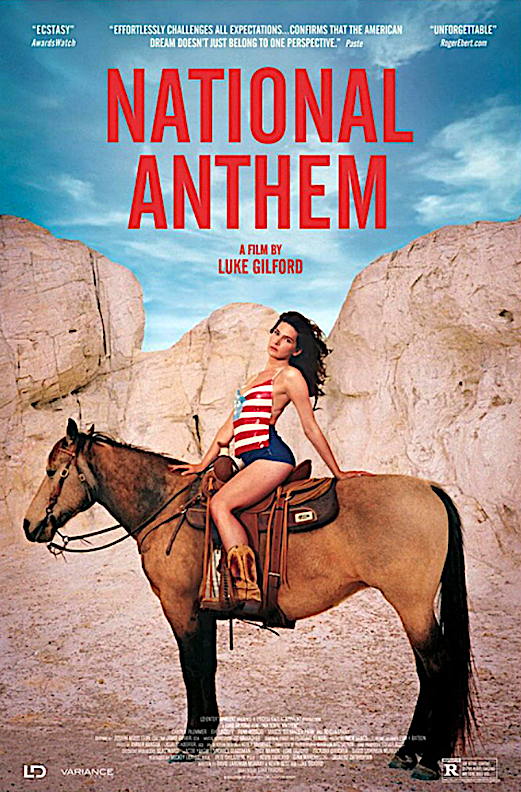

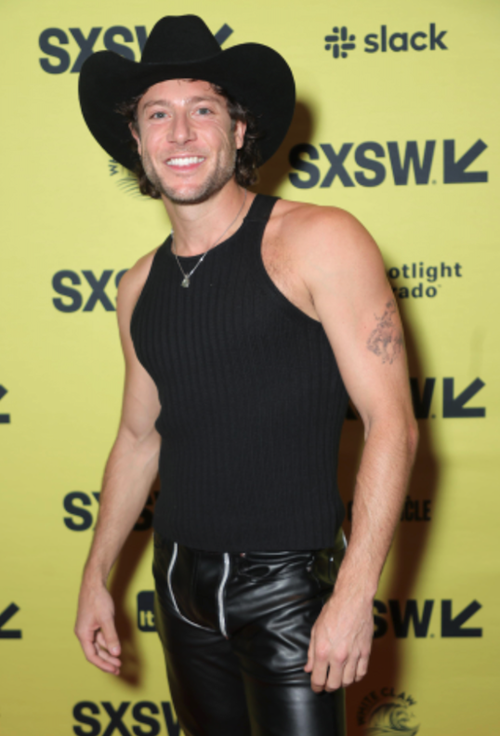

Recently featured at the Laemmle NoHo Theatre is Luke Gilford’s debut feature film National Anthem, a coming-of-age narrative of a different stripe. This beautiful film occupies a place in the imagination charged with nostalgia that chronicles a young man’s journey of self-discovery and acceptance in a gay community in the New Mexico hinterlands where director Luke Gilford once lived and there documented as. Photographer the queer community in the International Gay Rodeo Association, which is a real entity that is found across the United States. Gilford spent a couple of years traveling through Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona, documenting this vibrant sub-culture within a sub-culture. Gilford’s first feature film, National Anthem, takes place in this community. No wonder audiences have warmed to this film which recently received recognition at San Francisco’s Frameline Film Festival as Best First Feature Film for director Luke Gilford.

The concept of “chosen family” has much resonance for people whose actual families shunned or abused them. In this film, we discover the House of Splendor, a ranch populated by queer rodeo riders of all sexual/gender identities, and it is definitely a place of “chosen family.” The central character in this story is Dylan (portrayed with subtlety by Charlie Plummer), a 21-year-old young man who carries responsibilities far beyond his years. His mother (Robyn Lively) spends her nights drinking and bringing men home, leaving the care of Cassidy (Joey DeLeon), Dylan’s much younger brother, to Dylan. Dylan works as a day laborer. He cooks meals for Cassidy; he makes sure Cassidy does his homework, and he has conversations with him about things. He is tender with his brother, and patient. Dylan is saving up to buy an RV.

One day, he gets a two-week gig working at a ranch in the desert. From the back of the pickup truck transporting him there, he stares up at the words above the entry gate: House of Splendor. Within seconds Dylan realizes House of Splendor is not your ordinary ranch. He is struck by three women in billowy dresses riding horses. Everyone is working (driving tractors, feeding animals, gardening), but everyone looks happy. Dylan is captivated. Pepe (Rene Rosado), the rancher who hired Dylan, puts him to work without explaining “what country” House of Splendor is. The work is hard, but the atmosphere is friendly. Dylan gets an instant-crush on one of the horse-riding women, a trans woman named Sky (Eve Lindley), who clearly feels his interest in her and encourages it.

Dylan has never been exposed to anything like this, not just different sexualities, but people who are kind and respectful to each other. These happy people live together on the ranch, eat food they grow, take care of animals, and participate in rodeos on weekends. They include Dylan in all of this. The community seems like a LGBTQ utopia. We don’t get to know many people in this community, beyond Sky, Pepe, and the wonderful Carrie, played by Mason Alexander with such warmth and intelligence it emanates off the screen. Dylan develops a crush on Sky, seemingly without realizing that she is transgender. She is his first love, but Carrie is the guide, the warm mother figure (who also welcomes Cassidy to the fold on a day they all go to a county fair). All of these people, of course, have been through the trauma of non-acceptance from their families and the outside world.

These people who live on Pepe’s ranch are not just “survivors.” They are thriving. The rodeo is their world. They have created the world they want to live in. Gilford said in an interview, “One thing that I love about this community is that if you show up, you’re accepted. There’s something really beautiful about that. That’s what America is supposed to be.” Hence, the title National Anthem. Gilford’s cinematic eye is attuned to details, and there is a documentary feel to many of the sequences, particularly the rodeo scenes. These are the real people doing the real thing. He’s also attuned to Dylan’s awakening, as is Plummer, whose face is so open and transparent the camera catches everything. The dawning of love, of “finding his people” (as Sky observes), is everywhere on his face. Gilford and cinematographer Katelin Arizmendi help us enter this world by presenting it lovingly and intimately.

These people participate in all the “tropes” of Western life: ranching, farming, rodeo, line-dancing. The people in this community take their cowboy hats off and place them over their hearts for the national anthem. They do this without irony or snark. This is their culture, too, whether or not the mainstream accepts them. The visual language of the film is so strong, so poetic and palpable, it’s clear that National Anthem is not about whether Dylan and Sky will “make it” as a couple. National Anthem is about this shy young man “finding his people,” finding his chosen family.

In his introduction to the National Anthem monograph, Gilford wrote: “One of the great powers of the queer rodeo is its ability to disrupt America’s tribal dichotomies that cannot contain who we really are -–liberal versus conservative, urban versus rural, ‘coastal elite’ versus ‘middle America.’ It’s incredibly rare to find a community that actually embraces both ends of the spectrum.” National Anthem is an important film that might not have all the strengths of a great drama due to its meandering storyline, but the ideas and themes are consistently explored in a way that genuinely feels new.