By Robert St. Martin

Currently at the Laemmle Royal Theatre in West L.A. is Agnieszka Holland’s new film – Green Border (Poland, 2023). This profoundly moving, flawlessly executed multi-strand drama, shot in stark black and white, tracks refugees from various nations in 2021 trying to cross the border from Belarus into Poland. With inevitably tragic consequences, they become pawns in a gruesome game of “pass the parcel” between guards on both sides of the title’s green border, the dividing line between European Union member Poland and Russia ally. A searing drama about a European refugee crisis that resonates with similar crises in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and yes, America’s southwestern border, Green Border one of the most important films to be released in the U.S. so far this year.

The titular border is the one separating Poland from its neighbor to the east, Belarus. When we first see a portion of the border, filmed from an aerial angle, it is a spectacularly beautiful green, evidence of one of the last remaining primeval forests in Europe. But that visual beauty doesn’t last. Soon enough, the image shifts to black and white, and we enter a human world of violent oppositions and tragic ironies.

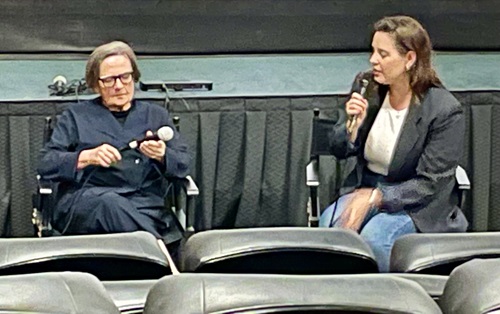

We were most fortunate to have director Agnieszka Holland present for a Q&A after the screening of Green Border. Holland always presents consequences with the context and circumstances necessary to understand their true impact. Her decision to shoot in crisp black and white hints at forces beyond the frame as well. Holland senses the same winds of fascism chronicled in her Holocaust-set films Angry Harvest (1985) and Oscar-winning Europa Europa (1990) blowing again across Europe. Like Pawel Pawliowski’s Ida a few years back in 2013, the moral seriousness and overall excellence of Green Border recalls the post-World War II apogee of Polish cinema. No surprise that Agnieszka Holland was mentored by two masters of that Renaissance, Andrzej Wadja and Krystztof Zanussi.

Green Border has not endeared the film or Holland to Poland’s leaders. One called Green Border “shameful, repulsive and disgusting.” Another likened the director to “Soviets and Nazis” who “used propaganda films to destroy the image of Poland and Poles.” Since the release of the film in Poland, Holland has had to employ bodyguards due to concerning threats against her. At the Q&A after Friday’s screening, she explained the impact of the film on Poland’s recent elections which ousted the far-right leadership of the country.

At first, we are on an airplane crowded with individual travelers and families, some dozing as others talks in excited anticipation of their expected goal: safety, freedom. They are refugees from places in the decimated east, such as Syria and Afghanistan. When the plane lands, the passengers spill out of the terminal and begin shouting into cell phones to distant relatives trying to help. A van arrives, people pile in. Kids in the group talk happily about how they’ll soon – hours from now? – be in Sweden. Adults caution that they must first enter the nearest European Union country, which happens to be Poland.

We first meet the focus of the film’s initial chapter. Buoyed up by relief and optimism, Bashir (Jalal Altawil) and his wife, Amina (Dalia Naous), are escaping Syria with their baby and their two older children, plus Bashir’s elderly father (Mohamad Al Rashi). Leila (Behi Djanati Atai), an Afghan woman travelling solo who asks to join the family on their journey to the border. The crossing – under cover of darkness and accompanied by grumbling gunfire in the distance – is nervy and uncomfortable. The border turns out to be a dense forest bisected by a wall of wire and barbed wire. When the passengers are dumped unceremoniously in this remote locale, they soon see that they are pawns in a deadly geopolitical game. Polish soldiers meet them only to push them back across the wire wall. There, Belarusians harshly eject them back into Poland. It is like a horrible, endless ping-pong game; one played for the highest stakes.

The crisis dramatized here is very real. It began in late 2021 when Aleksandr G. Lukashenko, Belarus’s Putin-allied, autocratic president, started offering free transit visas and transportation to people in the Middle East and Africa who wanted to reach Europe. His apparent aim was to inject a degree of destabilization into EU countries that were disinclined to accept an influx of refugees from distant, alien countries. Holland points out the racial/cultural dimensions of this resistance by noting that, only a year later, Poland generously opened its borders to two million refugees from neighboring Ukraine.

The refugees’ story is one of three major narrative strands in the film. Another follows a young Polish soldier and soon-to-be father (Tomasz Wlosok), who falteringly begins to grapple with the moral implications of “just following orders” when the consequences are so blatantly, irrefutably cruel. The story’s third strand concerns a disparate group of activists who invade the green border forests aiming to bring various sorts of help to the suffering, terrified refugees. You might think the Polish authorities would welcome any impromptu assistance that provided immediate relief where the need was so great. But the right-wing regime of Poland in 2021 instead determined that it was “at war” and that anyone who helped the refugees was aiding the enemy’s designs and must be arrested and prosecuted.

The script by Holland, Maciej Pisuk, and Gabriela Łazarkiewicz-Sieczko fashions the raw nerve endings of a still-unfolding situation into a multi-pronged panorama of the crisis. At the core is always the multinational group of refugees lured by the false promises of Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko for easy passage into Europe. Even as they fade from centrality to the narrative over the course of the sweeping two-and-a-half-hour runtime, Green Border never forgets that the migrants are the ones who bear the brunt of the pain. As Polish and Belarusian forces alike treat them as a political hot potato to be tossed across national boundaries, their Kafkaesque sense of dislocation moves from the realm of the physical into psychological.

In the film, politics are a distant abstraction. The only realities are the refugees’ desperation, confusion, disorientation, and stubborn determination even in the face of the brutality visited on them; Holland crafts vivid, compelling portraits of these unfortunates – including three generations of a Muslim family led by a crusty patriarch (Mohamad Al Rashi) who refuses to let danger separate him from his prayer rug.

The film’s scope widens with time to include more perspectives from Polish citizens, such as hardline border guard Jan (Tomasz Włosok) and largely apolitical psychologist Julia (Maja Ostaszewska) who lives near the “restricted zone” on the border. Jan is rebuilding an abandoned house near the green zone where his work as border guard is located. Julia who joins the fray when she hears a woman screaming for help outside her house one night. The woman she rescues, Leila (Behi Djanati Atai), is a spirited Afghan who has spent much of the story trying to help other refugees; ironically, she had planned to seek asylum in Poland.

Their necessity of the stories of Jan and Julia in the story is never in question – given that the average Western viewer is far more likely to see their own lives reflected through these characters. But the journeys that Jan and Julia undergo feature such obvious narrativization that they cannot help but feel a bit out of sync with the more observational and documentary-style segments featuring the refugees.

Julia’s presence in the film at least brings her into contact with activists helping within the border’s dangerous exclusion zone closer to her home. Like the refugees, Holland never portrays the group as a monolith. But these courageous organizations are often sanitized, if not outright sanctified, to provide paradigms of political participation for viewers to emulate. Green Border doesn’t shy away from the disagreement between sisters Marta (Monika Frajczyk) and Zuku (Jasmina Polak) as they debate how far their services should go. Holland shot the film, which chronicles the wide ripple effects of a 2021 surge of asylum seekers along the Polish-Belarusian border, in just 23 days in March of 2021 (during COVID). In the end, her sense of propulsive, incandescent outrage is both the project’s reason for existence and its strongest attribute.

Veteran director Holland is no stranger to political themes in her films. This most compelling film is a grim reminder of how wars have created a huge refugee migration. This on-going enormous issue in today’s world is brilliantly captured by the extraordinary artistry of Holland’s film. This is not an easy film to watch but worth seeing in this time of endless posturing by politicians about borders and migration of refugees seeking asylum. Winner of the Special Jury Award at the Venice International Film Festival in 2023 and several other awards at various film festivals, Green Border is definitely a film to see.