By Robert St. Martin and Valerie Milano

Palm Springs, CA (The Hollywood Times) 1/4/25 – Dahomey is a new documentary by filmmaker Mati Diop about the return of 26 important art objects from France to its former colony of Benin in Africa. Winner of the Golden Bear at the 2024 Berlin Film Festival, the film is included in the lineup at this year’s Palm Springs International Film Festival, beginning with a screening on Monday, January 6, 4:00 om at the Festival Theatres 6, Thursday January 9, 2:00 pm at the Mary Pickford 11-14, and Friday, January 10, 2:00 pm at the Palm Canyon Theatre. Dahomey was short-listed for Best International Feature Film at the 97th Academy Awards.

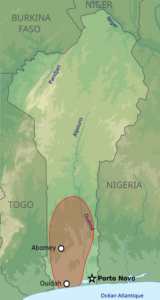

The Kingdom of Dahomey was a West African kingdom located within present-day Benin that existed from approximately 1600 until 1904. The African kingdom of Dahomey, which ruled over its region at the west of the continent until the turn of the 20th century, saw hundreds of its splendid royal artifacts plundered by French colonial troops in its waning days. Now, as 26 of these treasures are set to return to their homeland, filmmaker Mati Diop documents their voyage back.

The Kingdom of Dahomey was a West African kingdom located within present-day Benin that existed from approximately 1600 until 1904. The African kingdom of Dahomey, which ruled over its region at the west of the continent until the turn of the 20th century, saw hundreds of its splendid royal artifacts plundered by French colonial troops in its waning days. Now, as 26 of these treasures are set to return to their homeland, filmmaker Mati Diop documents their voyage back.

As with her layered, supernaturally tinged Atlantics, Diop takes a singular approach to contemporary questions around belonging in our postcolonial world, transforming this rich subject matter into a multifaceted examination of ownership and exhibition, and employing multiple points of view, including –most strikingly – those of the artifacts themselves as they sail in darkness over the ocean to their rightful home. The name “Benin” was adopted in 1975 because it was considered politically neutral for all ethnic groups in the country, while “Dahomey” was associated with the Fon people who lived in the southern half of the country.

The Kingdom of Dahomey was an important regional power that had an organized domestic economy built on conquest and slave labor, significant international trade and diplomatic relations with Europeans, a centralized administration, taxation systems, and an organized military. Notable in the kingdom were significant artwork, an all-female military unit called the Dahomey Amazons by European observers, and the elaborate religious practices of Vodun. The growth of Dahomey coincided with the growth of the Atlantic slave trade, and it became known to Europeans as a major supplier of slaves.

Alternating images of nocturnal melancholy and debates among students at Benin’s University of Abomey-Calavi about what should be done with the objects, Dahomey brilliantly negotiates a lost past and an unsure present. The documentary film blends facts and fiction to narrate the stories of 26 African artworks. The royal artefacts from the Kingdom of Dahomey (1600–1904) were taken to France during the region’s colonial (1872–1960). In the 21st century, they were put on display in the Musée de Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac a museum of non-European art located in Paris. Following a campaign for repatriation artefacts were returned to Benin in 2022.

Alternating images of nocturnal melancholy and debates among students at Benin’s University of Abomey-Calavi about what should be done with the objects, Dahomey brilliantly negotiates a lost past and an unsure present. The documentary film blends facts and fiction to narrate the stories of 26 African artworks. The royal artefacts from the Kingdom of Dahomey (1600–1904) were taken to France during the region’s colonial (1872–1960). In the 21st century, they were put on display in the Musée de Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac a museum of non-European art located in Paris. Following a campaign for repatriation artefacts were returned to Benin in 2022.

Among the returned works were statues of two kings of Dahomey, Glele and Béhanzin. Their throne, which had been seized by French soldiers in 1892, was also given back. The art pieces are now displayed in a museum in Abomey, the old royal city, about 65 miles from the Gulf of Guinea. The film includes a discussion by students at the University of Abomey-Calavi, presenting their views on the repatriation of cultural assets. Some of the students criticize the Paris Museum for returning only 26 of the 7,000 worldwide ethnographic objects it holds.

A prominent role in the film is given to the 26th art object to be repatriated, a statue that represents King Ghézo, who ruled from 1818 to 1859, shown below. A voice-over by Haitian writer Makenzy Orcel (who wrote this part of the script), playing the object, tells of the time it spent in storage at the Paris Museum, its memories of Africa and thoughts of returning to its homeland.