By Robert St. Martin

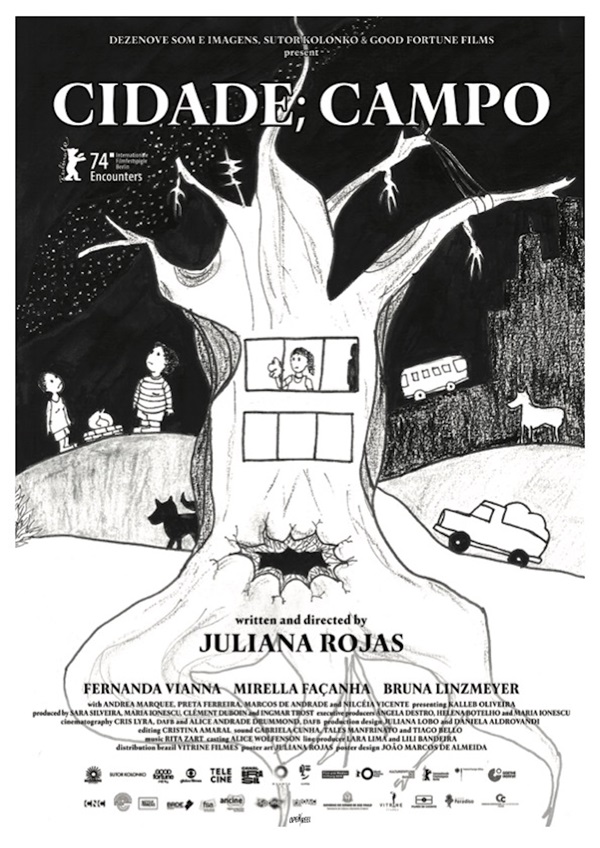

Los Angeles, CA (The Hollywood Times) 6/24/24 – A Brazilian film at this year’s Frameline 48 in San Francisco is Cidade; Campo (2024), directed by Juliana Rojas, recently took home the Encounters Award for Best Director at the Berlin International Film Festival.

Containing two different back-to-back stories, Cidade; Campo tells two tales of migration within Brazil – between the big city and the countryside. In first tale, a middle-aged woman named Joana (Fernanda Vianna) moves to São Paulo and tries to restart her life, after a disaster floods her land and the ensuing river of mud destroyed his home and farm in Minas Gerais. In the second tale: Flavia (Mirella Façanha) moves from Sao Paolo to a farm in the country with her partner Mara, after the death of her estranged father.

In the first tale, farmer Joana (Fernanda Vianna) arrives in Sao Paolo with almost nothing after the complete loss of her farm and home. She stays with her sister Tania (Andrea Marquee) and

Tania’s grandson Jaime (Kalleb Oliveira) after her hometown is devastated by floods. She still has nightmares about the destruction of her farm by the mud from the failed dam and the death of her beloved white horse Alecrim. We learn that the Mariana dam flood in 2015 was caused by mining mismanagement, which reflects real-life events in Brazil today.

In the bustling city, Joana grapples with the challenges of precarious employment. She takes refuge by tending to Tania’s rooftop garden and strikes up a relationship with Tânia’s young grandson Jaime (Kalleb Oliveira), who encourages her to begin working as a gig worker for a cleaning company. Joana learns to reinvent herself. Joining a cleaning company, she forms connections with her colleagues who collectively strive for better working conditions. Simultaneously, her bond with young Jaime stirs memories of her missing son.

In the second tale, Flavia (Mirella Façanha) and her lesbian partner Mara (Bruna Linzmeyer) move to a farm after the death of Flavia’s estranged father. He had always served as her base and moral support, and his death left in her feeling lost in a void – even because the two had been apart for some time. After her mother’s death, many years earlier, it became impossible for Flavia to continue on the family’s small ranch. Those who stayed then grew and matured each in their own way, and no matter how much they tried to keep in touch through occasional phone calls. Not the time has come to return.

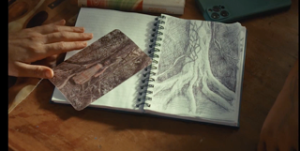

In the wilderness, Flavia and her partner (who is a seminarian) struggle to start anew, as they inhabit the abandoned farmhouse of Flavia’s father. There Flavia uncovers hidden facets of her father’s life. They experiment with ayahuasca after uncovering a book titled Mundos em Simetria (“Worlds in Symmetry”) and learning of her father’s interest in the psychoactive drug.

However, the harsh realities of rural existence shock the couple. Amidst the surrounding woods, Flavia begins to suspect something mysterious. An old friend of her dead father shows up and explains how he used to grow medicine herbs including the psychedelic Ayahuasca. In the nearby Amazon forest, Nature compels them to confront old memories and ghosts. The woman-friend of Flavia’s dead father knows all about the herbs and together they prepare a concoction to drink out on the edge of the forest. It is there that Flavia discovers that “a parallel universe is possible.”

Rojas’s two-pronged semicolon-ed work has social outcasts reckoning with physical and emotional estrangement in Brazil as they traverse the liminalities between the cidade (city) and the campo (countryside). Unfolding like a dialogue between its diptych parts, the film’s slowness is its strength, with a meditative but never dragging pace easing the viewer into contemplation between the stories that, by themselves, would feel unfinished.

The two parts of the film are made distinctly through camera work: In Joana’s world, the camera observationally peruses each scene, echoing her sentiment that “she likes to watch” other people as they go about their quotidian lives in the buildings across. In Flavia’s world, Rojas prefers slow zooms that confront her subjects and force them to reveal themselves.

If in the 20th century, the advent of industrialization led to a mass abandonment of rural areas who migrated to the big cities\in search of better living conditions and better income. In earlier centuries, the European immigrants who arrived in Brazil sought possibilities for cultivation and prosperity in lands not yet occupied in the interior of this huge country. In the 21st century, the direction of migration seems to go both ways. There are those who move from the city to the countryside and occupy voids left old people on farms dying. Joana and Flávia are both in different ways current examples of the face of a tomorrow that is increasingly difficult to predict.

Juliana Rojas had worked with supernatural elements in her previous works, and the same is true here. But in Cidade; Campo these supernatural appearances appear parallel to the real world, as it provides a guide to life. The women in Rojas’ films, as protagonists, care about the fathers who have left and, in Juliana’s case, the missing son she has not seen in years. These women reveal their strength during uncertainty.

Director Juliana Rojas’ solo work includes the award-winning short films O Duplo, which won a Special Mention at La Semaine de la Critique in Cannes, and The Passage of the Comet, as well as the feature film Necropolis Symphony, which won the FIPRESCI Prize at the Mar del Plata International Film Festival. Collaborating with Marco Dutra, she wrote and directed the short films The White Sheet, A Stem, The Shadows and We Were Born Today, and the feature films Hard Labor and Good Manners, the genre-hopping lesbian were wolf film that won the Special Jury Award at the Locarno Film Festival.

Cidade; Campo screens at the Roxie Theatre in San Francisco on Tuesday, June 25 at 6:00 pm. For tickets, go to: https://www.frameline.org/films/frameline48/cidade-campo