By Robert St. Martin

Los Angeles, CA (The Hollywood Times) 6/20/24 – On Thursday, June 20, at the Theatre in San Francisco, Frameline 48 was a screening of Barnaby Thompson’s well-researched documentary about the British playwright Noël Coward – Mad About the Boy: The Noël Coward Story. This BBC-financed documentary is an affectionate portrait of one of England’s most quintessential playwrights of the Twentieth Century – Noël Coward, universally known as “The Master” and famous as a playwright, composer, director, actor, and singer – as well one of the wittiest flamboyant men of his generation.

Although Noël Coward (1899 – 1973) is still famous, there may well be a younger generation for whom a resumé of his many achievements will be informative while the old clips seen here – from films, interviews, cabaret performances and even old home movies – will be a welcome reminder of past pleasures for those viewers who are older. Mad About the Boy derives its title from a 1932 song written by Noël Coward for a musical revue and later made famous by singer Dinah Washington. The song deals with the theme of unrequited love for a film star. It was written to be sung by female characters, although Coward (who was a gay man) also wrote a version which was never performed, containing references to the then-risqué topic of homosexual love.

The documentary Mad About the Boy feels like a routine scissors-and-paste job relying as it does exclusively on archive be that in black and white or in color, some of which are photographs and home movies shot by Coward himself. In this day and age, the film can be frank about Coward’s homosexuality: It references his relationships with Jack Wilson and Alan Webb for example. It also brings in two significant voices, his long-term companion Graham Payn and his secretary Cole Lesley, but these are inevitably old comments and the only real insights into Coward’s life as a gay man stem from his private thoughts in his diaries.

Noël Coward was a completely self-made man having come from a poor working-class family to then eventually being the toast of ‘high’ society. He started out as a child actor at the age of 12 in 1911 and was so successful that he very soon became the breadwinner for his entire family. Along the way he lost his childhood stutter and gained a plummy accent that became one of his signature hallmarks.

He had been writing his own plays since the age of 12, and he took most of these scripts to try and interest American theatrical producers. He had little luck but was sharp enough to observe how different American comedies were, and adopting this style he wrote The Young Idea which gave him his first real success in London.

Just 3 years later in 1925, Noël Coward then had his first great critical and financial success as a playwright with The Vortex. Its controversial story was about a nymphomaniac socialite (played by Lilian Braithwaite) and her cocaine-addicted son (played by Coward) all considered very shocking in its day. Sharp-eyed critics saw the drugs as a mask for homosexuality, but it played to packed audiences, and repeated its success when Coward took it to Broadway. For that production, Coward chose young John Gielgud as his understudy in The Vortex. For the last month of the West End run, Gielgud took over Coward’s role of Nicky Lancaster, the drug-addicted son of a nymphomaniac mother.

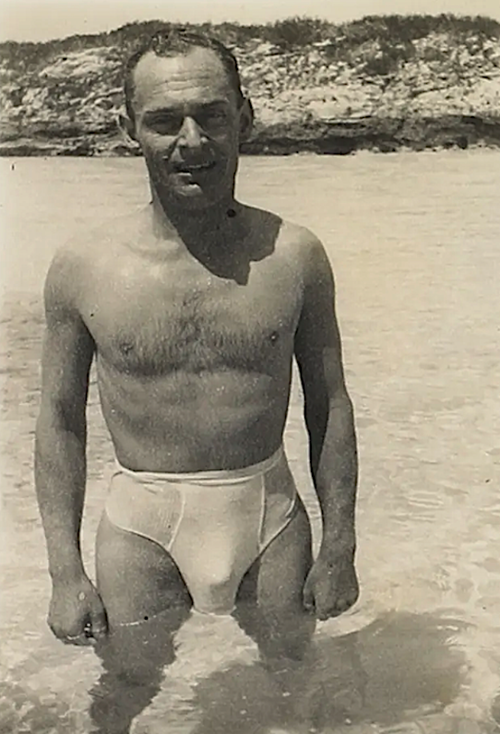

This was also the time of Coward’s first gay live-in lover. Jack Wilson first met Coward at a performance of The Vortex, Wilson was an American stockbroker who became Coward’s manager, but he developed into an alcoholic and proved unfaithful, eventually robbing Coward blind. In the 1930s, Noël Coward cast actor Alan Webb in his Tonight at 8.30 and began a stormy affair with him; we have long-hidden photographs of them from their time in the Bahamas. Sadly, the film reveals nothing about the personal life of Noël Coward and his lovers. Coward invented himself and was always in performance mode of “Noël Coward,” the seeming British aristocrat and society playboy.

The success of The Vortex marked was the start of Coward’s meteoric rise to fame. By June 1925 he had four shows running in the West End: The Vortex, Fallen Angeles, Hay Fever and On with the Dance. But the downside of this was that his frantic pace caught up with him and he collapsed on stage starring in The Constant Nymph in London. He ignored the doctors and sailed for the US to start rehearsals for his next play, but he decided to set sail for Hawaii and rest.

In his documentary, Thompson details the roller-coaster track of Coward’s professional life. By 1929 Coward was one of the world’s highest-earning writers, with an annual income of what today would be £3 million. Coward was a long-time friend of both Laurence Olivier and his lesbian wife Vivien Leigh. Laurence Olivier’s stage career was practically launched by Noël Coward, who gave him the part of Victor Prynne in Private Lives in 193 In the 1940s, Coward teamed up with director David Lean to produce two films, Brief Encounter and Blithe Spirit.

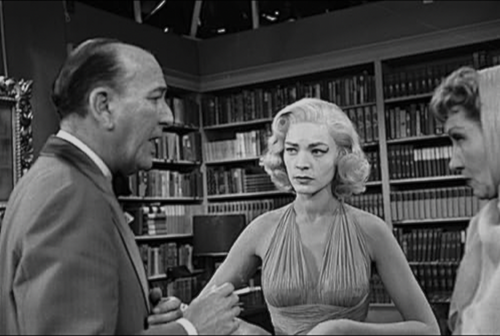

Coward’s most enduring work from the war years was the hugely successful 1941 comedy Blithe Spirit, a play about a novelist who researches the occult and hires a medium, who in turn brings back the ghost of his first wife during a seance, causing havoc for the novelist and his second wife. With 1,997 consecutive performances, it broke box-office records for the run of a West End comedy, and was also produced on Broadway, where its original run was 650 performances. The play was adapted into a 1945 film, again written by Coward and directed by David Lean. In 1956 Noël Coward starred with Claudette Colbert, Lauren Bacall, and Mildred Natwick in a Live TV production of Blithe Spirit.

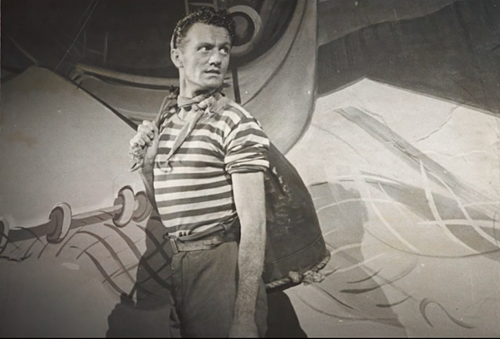

During World War II, he was recruited as a British Spy, a fact kept from the general population, but evident known to Hitler as he had included Coward on his “Must Be Killed’ List. Another of Coward’s wartime projects, was as writer, star, composer and co-director of the naval film drama In Which We Serve. The film was popular on both sides of the Atlantic. The King wanted to reward him with a Knighthood, but Churchill refused on a petty excuse that Coward had once contravened currency regulations but more likely it was because of Coward’s “closeted” homosexuality.

After World War II, Coward soon discovered that his new plays were considered dated and out of style and were not well received at all. They would eventually be replaced with the mew kitchen-sink dramas by the likes of John Osbourne and Harold Pinter, for which Coward made no secret of his distaste. Down in his luck and in debt, he decided to perform some of his best songs at the cabaret club Café de Paris in London. It was an unprecedented success and soon he had an offer to take the show to Las Vegas where the packed audiences loved his very Englishness.

He was back on top again professional and personally as since 1945 he had a new younger lover/partner in South African-born Graham Payn and they would be together right up to Coward’s death. Again, nothing is shown or explained about that long-term relationship in the film. Coward continued to act on stage and in films as well as writing new plays and musicals. During this period, he won new popularity as an actor in films, including Around the World in Eighty Days (1956), Our Man in Havana (1959), Bunny Lake is Missing (1965), Boom! (1968), and The Italian Job (1969). Notably, he turned down the role as the title character in the 1962 James Bond movie, Dr. No.

In the late 1950s, Coward spent time in Jamaica and fell in love with the beauty of the island. He bought the Firefly estate in Jamaica, which was once originally owned by the pirate and one-time governor of Jamaica, Sir Henry Morgan. There he was neighbors with Ian Fleming, and he entertained a wide range of guests at Firefly, including both the Queen Mother and Queen Elizabeth II, Winston Churchill, Laurence Olivier, Sophia Lauren, Marlene Dietrich, Elizabeth Taylor, Alec Guinness, Peter O’Toole, Richard Burton and Errol Flynn. He made Jamaica his home until his death in 1973.

In 1966 Coward abandoned his customary reticence and played an explicitly homosexual character in A Song at Twilight. The daring piece earned Coward new critical praise and was just one year before the Sexual Offences Act in the UK was passed finally legalizing homosexuality. Coward had been closeted publicly and even in the 1960s refused to acknowledge his sexual orientation publicly, wryly observing, “There are still a few old ladies in Worthing who don’t know.” Despite this reticence, he encouraged his secretary Cole Lesley to write a frank biography once he was safely dead.

Mad About the Boy features the voices of Alan Cumming and Rupert Everett, but all the talent does not fill in the gaps in the personal life of Noël Coward about which we learn little. He is always in performance mode, so we never really get to know the man from the inside out. The film was part of the opening night offerings at Frameline 48 on Thursday, June 20, at its screening at the Roxie Theatre in San Francisco. If you missed it, you could still see the film online courtesy of Frameline’s Digital Screening Room, beginning June 24.