By Robert St. Martin

Westlake, California (The Hollywood Times) 05/09/2024

Some of the strongest documentary films from Southeast Europe find their way in the annual SEEfest Film Festival. One of these that screened on Sunday at UCLA Bridges Auditorium is Motherland, an ominous portrait of the oppressive culture of cruelty in Post-Soviet Belarus. This slow-burn documentary follows a young Belarusian embarking on compulsory military service and a mother seeking justice for her son, who died during his service. Belarusian filmmakers Alexander Mihalkovich and Hanna Badziaka descend into the country’s underbelly of military culture in their latest work, Motherland. The documentary doubles as an inquiry into the traumatic, decades-old tradition of violent bullying among Belarusian military conscripts. The mechanism proved to be a tried and tested tool for discipline-forging and manipulation. Yet it came at the cost of several young lives.

The film follows a woman named Svetlana as she grapples with the loss of her son Sasha, who was found hanged on an army base two years prior. She seeks justice by prying the authorities to properly investigate the death, which she is certain was caused by severe bullying. Svetlana meets parents with a similar fate, exposing the mechanisms of control that go unchecked. While it seems that she is battling not only bureaucratic windmills, but her also seemingly futile endeavor further unveils the functions of a totalitarian state.

As a counterpoint to Svetlana, a young conscript named Nikita is about the embark on his compulsory military duty and experience the insidious world of post-Soviet Belarus on his own skin. The practice that might have been originally devised to turn boys into men instead perpetuates generational trauma deeply ingrained in the nation’s contemporary culture. And society at large appears to know about it and tolerate it.

Nikita and Svetlana’s poignant narratives mirror the burgeoning rage on the streets, as the state-sanctioned violence morphs into the government’s primary tool to instill fear and maintain domination over its citizens. Badziaka and Mihalkovich utilize the protagonists as a representative of their generations, mothers, and sons, to depict a disturbing portrait of present-day Belarus and the modus operandi of an authoritarian state.

Motherland serves as an examination of a troubled nation grappling with its own dark history and the devastating repercussions of its unchecked power. The investigation unfolds against the backdrop of the disputed re-election of dictator-president and Putin sympathizer, Aleksandr Lukashenko, the protests that erupt in the streets in the aftermath, and the police suppression of the riots.

A distinct documentary approach defines Nikita and Svetlana’s narrative. Badziaka and Mihalkovich remain silent observers in both cases. Svetlana’s part follows a single thread to unveil her son’s murderers and has more of an investigative nature. On the other hand, Nikita serves as a first-hand witness, relaying almost in real time what is happening in the barracks. Yet military bullying is just a symptom of a bigger diagnosis.

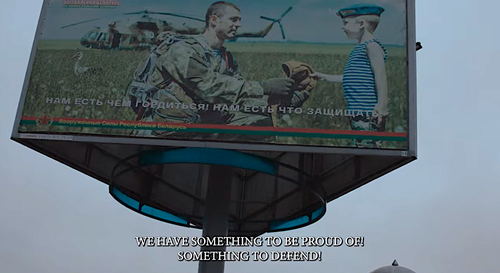

The very first words in the Belarusian national anthem, which is being sung devoutly at an army graduation ceremony as Motherland begins, are “We Belarusians are peaceful people.” It does not take long for the irony to bite. Grave skies heavy with snow frame the stark beauty of Siarhiej Kanaplianik’s camerawork, as Hanna Badziaka and Alexander Mihalkovich’s handsome, bitter film outlines something close to the inverse of that ideal: a culture of brutality, bullying and complicity that is fostered in the Belarusian military, and then seeps like the cold into the very bones of civilian society.

Dedovshchina as some terse titles explain, translates to the benign sounding “rule of Grandads.” But it describes a systematic code of psychological and physical abuse visited on new conscripts by their longer-serving colleagues, that the Belarusian military establishment, like that of other former Soviet countries, inherited from the Russian army. Most of the time, dedovshchina can be characterized as a particularly violent and humiliating form of ritual hazing, designed to break any spirit of independence or rebellion in newcomers.

Having understood that conformity is their best survival tactic (even at that first graduation ceremony, onlookers remark that they cannot pick their own sons out of the lineup: “They kind of all look the same”), last season’s victims become the next cycle’s perpetrators, before they matriculate back into the general population, carrying with them the harsh lessons they’ve learned about might being right, and submission to authority being an inescapable fact of life.

Sometimes, as in the case of Svetlana’s son Sasha, deaths result. Sasha was found hanged, his death classified as a suicide, but that did not account for the bruises and ligature marks that covered the body that Svetlana received. In the years since, she has dedicated herself to exposing dedovshchina and prosecuting those responsible for Sasha’s violent end. We follow Svetlana on galvanizing visits to other afflicted, grieving parents, as they discuss, with heartbreaking directness, the similarity of their callous, stonewalling, deceitful treatment by the authorities.

We also meet Nikita, a young man with a hipster mohawk and a tight-knit circle of partying buddies who has just received his conscription order and, unlike many of his peers, has decided not to flee or “pull a nutcase” to get out of it. He discusses his fears with his father, who has an old-timer’s respect for the discipline and direction he believes the training will instill in his son. But as the months of his service pass, Nikita becomes increasingly estranged from his friends, which is highlighted when they participate in the protests that follow the 2020 re-election – widely considered illegitimate – of Belarusian leader Alexander Lukashenko, and Nikita’s is one of the units called in to suppress the demonstrations.

When Nikita finally returns home, he confesses to being wholly messed up by the experience – he is not as irrevocably lost a son as Sasha is, but he is lost, nonetheless. Motherland mourns many losses. Not just the extinguished spark of young lives like Sasha’s, and the eradicated individualism such as Nikita experiences, but the slow sapping of the energy it takes to fight an unjust and corrupt system. Belarus may not be at war, but as the quietly, elegiacally agonized Motherland demonstrates, this nation of “peaceful people” is hardly at peace either.

This is a remarkably quiet, introspective film interwoven with fragments of a murmured voiceover reading letters from a soldier to his mother that are based on those Mihalkovich wrote to his own mother.