By Robert St. Martin

Los Angeles, California (The Hollywood Times) 02/26/2024

Friday at the Billy Wilder Theatre of the UCLA Hammer Museum, there was a special screening of the award-winning film I’m No Longer Here (Ya no estoy aquí, Mexico, 2019), which was Mexico’s international film Oscar submission in 2021, the year that COVID arrived. Mexican director Fernando Frías de la Parra tells several stories in I’m No Longer Here. The film follows the leader of a street gang in Monterey, Mexico, who abandons a life of cumbia music and dance and flees to New York when he falls foul of a local cartel. This Mexican movie set between Queens, New York, and Monterrey, Mexico is a stunning and profound work of art. A theatrical run was set for the film but ultimately the COVID pandemic scuttled these plans, and the film debuted on Netflix in May 2020, where it can be viewed.

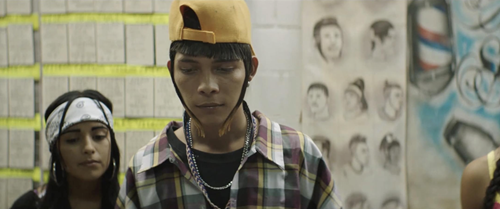

17-year-old Ulises played by a confident Juan Daniel García Treviño is the leader of a street dancing group that loves Cumbia, the Afro-Colombian style of music that has popularity in some parts of Mexico. Dancing is an alternative to being sucked into gang life, which Ulises and his crew have ties to. Ulises is a fierce dancer, and his town starts noticing. But just when his community is flourishing and his slow cumbia dancing is becoming famous, a wrong-time/wrong-place situation has a gang force him to leave everything behind and immigrate to the U.S. He suddenly finds himself lonely and living a life of undocumented existence in ethnically mixed Jackson Heights in Queens in New York City.

Ulises ends up doing day laborer work in the shadow of planes landing at LaGuardia Airport. As comfortable and connected as he was in his neighborhood back home, he’s lonely and isolated in the United States. He doesn’t speak any English but even the Spanish speakers he works and lives with ridicule him for his looks, his accent, and especially his taste in music, which is crucial to his sense of self. Frias captures the surreal sensation of feeling utterly alone despite constantly being around people as Ulises struggles to find his way in a foreign land.

But he strikes up an unexpected friendship with Lin (Angelina Chen), the pretty and inquisitive 16-year-old granddaughter of the Korean convenience store owner for whom he does odd jobs. The scenes in which she tries to speak with him in halting Spanish, even going so far as to communicate with him through Google translate while sitting next to him at a library computer, have an understated sweetness about them. But ultimately, he does not fit in and ends up deported back to Mexico. But his return to Monterey comes at a cost.

I’m No Longer Here focuses on modern teenagers in the northern Mexico City of Monterrey who are obsessed with the bouncing beat of traditional cumbia music, slowed-down and done their own way. They call their crew the Terkos, go by nicknames like Chaparra and Sweatshirt, and spend their days wandering the streets, singing, dancing, and talking trash about the other groups in town. “The essential point of the film is that Ulises and his friends are just like the slowed-down cumbia – they are like a metaphor for a very fast expiring youth,” says the filmmaker.

Director Frias, working with cinematographer Damien García, follows the non-actors playing these characters in long takes as they roam narrow, graffiti-strewn alleys and climb around the beautiful decay of abandoned construction sites. They allow us to revel in the teens’ signature style as they move to the beat. Their baggy, brightly hued street gear and their haircuts which are spiky on top and long in the front with dipped blonde tips. And when they dance, it’s a cool and specific mix of the ancient and the timeless: The boys prance like roosters while the girls playfully shake their butts. It’s a primal mating dance but it’s also refreshing and alive – capturing the sexual energy of what was originally a Colombia slave dance.

“If you look at the way they dance it in Colombia, it’s fast and they take short steps because the slaves’ feet were tied together and that’s why they had to do these kinds of dances,” says Frías de la Parra. So, they adopted it in Monterrey, and as the years went by and the war on drugs intensified, these communities were fertile ground for crime groups. This darker version of slowing the dance down reciprocated the darkness that the city was living in.” The filmmaker first learned of the slowed-down cumbia scene in Monterrey when a friend brought him a CD. Cumbia is a musical style that evokes nostalgia and what guides Frías’ film are the powerful emotions that Ulises experiences and portrays in movement and dance – and ultimately his own nostalgia for cumbia culture.

“I love glitches and cultural accidents, and counterculture itself inherently is always a mix of things,” he says. “I’ve always told stories about culture clash, the fish out of water.” As Frías de la Parra pursued his research, he learned that Monterrey’s cumbia culture is slowly vanishing as cartels kidnap children and force them into servitude. “Eventually kids were raising their hands to join, and that’s what my character sees when he’s in New York – he sees his friends proudly posing with the guns [on social media].”

That was an impetus to tell I’m No Longer Here, which was produced by Mexico’s Panorama Global and PPW Films from the US and is Frías de la Parra’s second feature following Rezeta, winner of the 2014 Slamdance grand jury narrative feature award. The director’s latest film also dovetailed with his desire to portray people on the margins of society. Frías de la Parra became familiar with stories of violence while teaching workshops to youngsters in rough areas of Mexico to pay off his university loans. “One kid told me he would never reach my age,” he says. “Back then, I was 33. That shocked me. How can we judge people who choose to work at the margins of what is lawful, or who join organized crime, if there are no opportunities in Mexico or Latin America?”

Frías de la Parra was determined to eschew the “misery porn” depiction of ultra-violence that has become emblematic of much of Latin American life on screen. “I had never connected with the way the violence in Mexico was being portrayed in narratives,” he says. “It had become an export product, like something designed for European festivals… I always wondered how characters are portrayed in films that do well internationally and how do people similar to these characters relate to them.”

As Frías explained at the Q&A at the UCLA Hammer on Friday, “I wanted to see if there was another, more humane way of portraying people that seemed more honest,” he continues. “A way to connect the dots of reality and make a film about the inner conflict of a coming-of-age kid who has to be displaced.”

Frías de la Parra began writing the story in 2012 for his university thesis. Although his tutors did not warm to the idea, the story would not let him go, and he secured development support for the project from Sundance Institute’s 2014 screenwriters and creative producers lab. It also received financing from Imcine, and additional support from Cinereach, San Francisco Film Society, Ventana Sur’s Primer Corte, Los Cabos Film Festival, Guadalajara International Film Festival and Bengala.

Production got underway in Monterrey in late 2017 and lasted four weeks before a lack of funds and the onset of winter brought everything to a halt. Bureaucracy also played its part – it was proving difficult to get newcomer Juan Daniel Garcia (Ulises), a drummer whom Frías de la Parra had spotted playing the timbales at a municipal show, into the US. “Every time [Juan] went to the consulate to get the visa stamped, he would get rejected,” the director recalls. “We had half of the film shot already and I was almost panicking. I was asking myself, ‘Would I have to walk through the desert [across the US border] with him?”

During the hiatus there was a game-changing stroke of luck: Netflix executives heard about the project, met with the filmmakers and came on board as financiers. With money in place and the star’s papers in order, I’m No Longer Here resumed production in Jackson Heights in the New York borough of Queens in July 2018 for 15 days. Frías de la Parra started post-production the following month, took a break to direct six episodes of HBO’s Los Espookys and completed the film in August 2019. Since then, Frías has made another film I Don’t Expect Anyone to Believe Me (No voy a pedirle a nadie que me crea, Mexico/Spain, 2023). Budding actor Daniel García Treviño has found his way into other films, including Amat Escalante’s thriller Perdidos en la noche (Lost in the Night, Mexico, 2023) which was included in the AFI FEST in Los Angeles in November 2023.